It is Dyslexia awareness month and I hope you are gaining a deeper understanding of this condition which impacts up to 20% of the population. Before discussing the importance of early identification, let’s review several points that were made in previous articles in the series.

1) Dyslexia is a reading disability that impacts the individual’s ability to identify and recognize print at the word level and exists on a continuum from less to more severe

2) Brains are all different, and we have evidence that “dyslexic brains” differ in subtle ways from birth. (see graphic below)

3) The brain is not pre-wired for reading, so every time a child learns to read, a “reading circuit” must be constructed in the brain.

4) Instruction and practice are the engines that build the “reading circuit.”

5) Carefully structured, targeted, explicit instruction is the best offense against dyslexia.

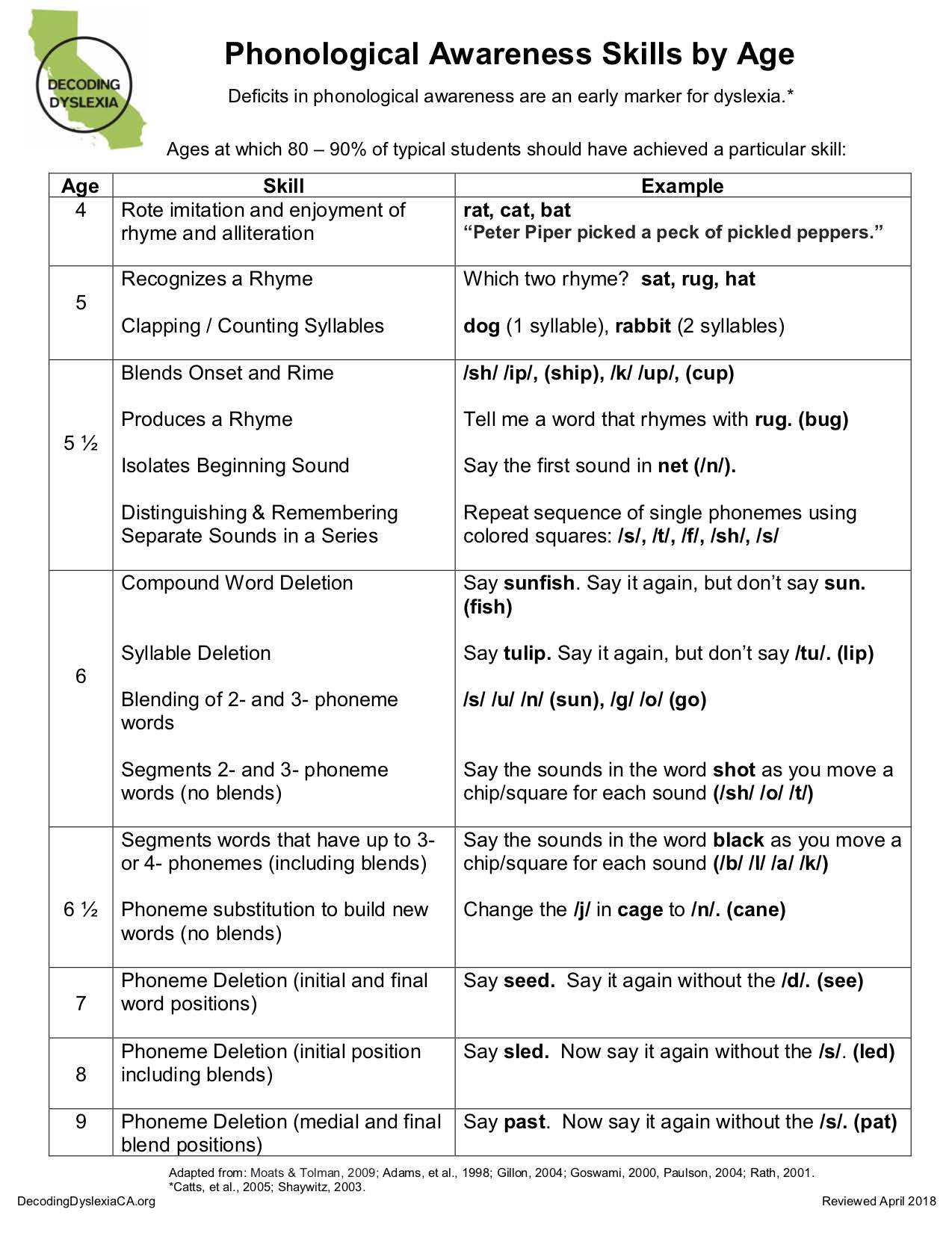

We know that virtually all dyslexic children do poorly on measures of phonological awareness, their ability to process the speech sounds in language (as shown above). The chart below identifies phonological awareness skills in a developmental sequence. If a child has not grasped a particular skill by the age suggested, it might be cause for some concern. Most of these skills emerge earlier than the ages provided in typically developing children who are exposed to a rich language environment that primes the child’s brain for reading.

The dyslexic child may also be immersed in a rich language environment, she too may be hearing stories and rhymes and learning songs, but for reasons we do not clearly understand, the parieto temporal region (blue) is not activating and developing in response. Typical preliteracy activities are not working their “magic” with her. She will require more targeted and explicit interactions designed to teach these phonological awareness skills if the beginnings of a reading circuit are to emerge in her brain.

When our children enter kindergarten, we commence formal reading instruction, but the dyslexic child is already behind. He is unable to perform basic phonological processing tasks that are prerequisite to learning to decode words with phonics and building a sight vocabulary that permits fluent and accurate reading. He does not benefit from the instruction that is provided in the typical kindergarten classroom. The reading circuit development is stalled and this child, desperate to learn to read and keep up with the class, tries and tries, with little success. His efforts build and reinforce an ineffectual reading circuit. Now, we have a child who

is making minimal progress in reading and spelling and his continued efforts, performed ineffectively, are exacerbating the “damage.”

There is some good news though, because we have the know-how to identify children who are at risk for dyslexia early in their formal education. Once identified, we can deliver interventions, first in the general education setting, and later, if needed, in more restrictive settings to improve outcomes for at-risk children. We know it is possible to get a good half of our at-risk children up

to or near grade level. But we must intervene before the child establishes inefficient, ineffective habits that are difficult to break and we need to take advantage of maximum brain plasticity. Younger primary grade children’s brains are more malleable and adaptable before age 8.

About 40 states have passed legislation requiring early universal dyslexia screening of all public school children. Most of this legislation also mandates intervention. Screenings are differentiated and age-appropriate, though each state is a little different. In kindergarten screenings usually include, at a minimum: alphabet knowledge, letter sounds and phonological awareness assessments. As children advance through the year and the primary grades, additional assessments like phonics inventories and sight word evaluations are added. Depending upon the state, the screenings continue through second or third grade. Early

identification is our best hope for improving outcomes for children who are dyslexic. Under the current system, children are typically identified late in second or in third grade. Delaying meaningful intervention this long reduces effectiveness and dooms more children to a lifetime of semi-literacy, and this has many hidden costs to the child and society.

Senate Bill 237, mandating universal dyslexia screening and intervention for at-risk students in the primary grades was introduced on 1/21/21 by Senator Anthony Portantino. While there was much support for the bill and many of us had high hopes, it was not to be. The bill was “killed” in early July and will have to be re-introduced next year. I would like to take this opportunity to

urge each of you to please contact your state senator and ask him or her to please support the next incarnation of this bill. I recently did just that and my senator responded with an encouraging letter of support for the effort. It is not okay for California to lag behind almost every other state in serving the needs of our dyslexic children. Your support is appreciated.

Julia Lewis is a Reading Specialist and Special Education Teacher

This article is part of a four-week series Macaroni Kid Upland, Claremont & La Verne is featuring on Dyslexia this month. We hope to bring awareness and education regarding dyslexia to our community. For more information regarding dyslexia visit Decoding Dyslexia

Part One: What Is Dyslexia?

Part Two: Dyslexia Awareness?